Interview: Poet Jay Baron Nicorvo on 'Deadbeat'

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

The scholar John Rodden calls the literary interview a “fully-fledged genre.” I used to be skeptical, but after assigning my students at The College of Saint Rose to speak with an author, I’m more inclined to think the literary interview qualifies as a distinct form of performance. I put out a call on Facebook and Twitter: Would you speak to a college student about your book? I asked. Sure, they said. Review copies were sent, students selected authors, read and researched their work, and asked questions. - Daniel Nester, Contributing Word Editor |

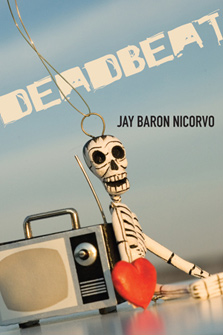

POET JAY BARON NICORVO ON HIS DEBUT, ‘DEADBEAT’ |

||||

INTERVIEWED BY

|

In his debut book of poems, Deadbeat, Jay Baron Nicorvo shares his struggles coming to terms with his relationships with his father and his transition into becoming a father himself. It is pure, raw, and cutthroat poetry. The first deadbeat dad was none other than God, he says. With dreams of his son becoming a great man and him being the best father, he’s set his sights high, and Deadbeat is one of the first steps to reaching those goals. We spoke over email, he in Michigan and me in New York. MAR SHAY HINES: As soon as I opened your book, I was enticed to read more because of this quote from Fyodor Dostoevsky: “These young men do not understand that the sacrifice of life is, perhaps, the easiest of all sacrifices.” What do you think the sacrifices of life are and why? JAY BARON NICORVO: That’s a wonderful question, Mar Shay, and not an easy one to answer. HINES: What influenced you to write the powerful poem, “Child Support Hearing”? NICORVO: That’s a very personal poem, about as confessional, as autobiographical, as my poetry gets. I last saw my biological father 26 years ago at a child-support hearing; that scene inspired the poem. The man responsible for my life, and the lives of my two younger brothers, showed up to court looking homeless to convince the presiding judge to reduce his monthly child-support payments. It worked. I was ten years old, and in addition to it being the last time I saw my father, it was also the first time I’d ever seen him without his toupee! NICORVO: In intimate company, I sometimes find myself saying, “I’ve been unlucky in fathers but lucky in father figures.” John Skoyles, one of the finest people I’ve ever met, is a poet and memoirist. He was the chair of the writing, literature, and publishing department at Emerson College when I was earning my MFA there, and John treated me more like a son than a student. That poem, “A Long, Precarious Walk,” which I’ve come to see as a kind of parable of my prosody, came out of a conversation John and I had at Remington’s of Boston next door to the college. He took me to dinner, told me stories about Denis Johnson and Robert Creeley, and offered me sound advice on everything from writing to hygiene. Which reminds me. I came into his office one day, and before I had my bag off my shoulder he asked what size sport coat I wore. I said I didn’t know. I didn’t own any sport coats. I was 24 and grew up hardscrabble, working-class. I’d never owned a sport coat. I went home and looked up this “Don Rickles,” and I spent the next ten years tightening the loose screws in my verse. HINES: You stated, “For my Father whomever you are and for my son whomever you may.” What would you tell men who are becoming fathers? What did you tell yourself before becoming a father? NICORVO: Do your damnedest to be sure you’re ready for fatherhood, because if you’re not and you fail in your duties, you’re going to fuck it up for everyone, everyone in the family, everyone in the community, everyone in the country. That’s not hyperbole. When a father doesn’t support his kids, in this country at least, the responsibility often falls to the government. HINES: What was the force behind Deadbeat becoming your debut? NICORVO: Madness. I wrote and rewrote it off and on for a decade. I didn’t want to be the Don Rickles of the poetry world! If I were sane, I would’ve given up on it much sooner. NICORVO: Along with an “Acknowledgements” page, a lot of poetry collections these days include a “Notes” section, where the poet explicitly states allusions and lists sources cribbed. Part of me hates those notes sections, though I read them. I hear therein the insecurity and the insincerity of a gloat. James Joyce’s Ulysses, like Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” has generated a wealth of academic criticism and scholarship. Even Joyce’s friends urged him to write an explanation of the book. His response: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of ensuring one’s immortality.” This is all to say that I wanted the titles and epigraphs (and even the titles of the books from which the epigraphs come) to be suggestive of themes in Deadbeat, while at the same time offering a roadmap to a few of my influences without me having to say, “You, go here. Read this. Ain’t I clever?” HINES: You used Psalm 22, “Why hast thou forsaken me? Why art thou so far from helping me, and from the words of my roaring?” Did you use it based on religious values or as if it was a piece of poetry in a book? NICORVO: Both! I was raised Catholic, though I’m now a devout heretic, and the King James is pure poetry. But I was using that psalm to suggest that the first deadbeat dad was none other than God. HINES: How did you and Matthea Harvey choose that piece of artwork as your cover photo? That photo speaks volumes. NICORVO: When the book was accepted, the Four Way Books publisher, Martha Rhodes, asked me to recommend art for the cover. I wanted an image that, like the poems in Deadbeat, and like the central character himself, came close to capturing a reflection expressed by Stanley Kunitz: “Years ago I came to the realization that the most poignant of all lyric tensions stems from the awareness that we are living and dying at once. To embrace such knowledge and yet to remain compassionate and whole—that is the consummation of the endeavor of art.” I thought of Matthea, who’s a friend. She has a fascination with all things small, and I knew, from conducting a public interview with her, that she was working on a series of poems with close-up images of tiny things in lieu of poem titles. I begged her to take pictures of little Deadbeat. She agreed and went to work. Four or so beautiful images came out of the shoot, she snapping the pictures while her husband, Rob Casper, played puppeteer. The cover image was the one Matthea liked best, and Martha and I agreed, but the other images that didn’t make the cut are wonderful, too. Thankfully, they’ve had a second life, first as a collaboration we did for Abe’s Penny, a literary journal on postcards that pairs poetry with images, and then as background images for the website I cobbled together for myself. HINES: How is it working with your wife, Thisbe Nissen? NICORVO: It’s blessed. Thisbe saves me from myself. She’s my best friend, my first reader, a writer of the highest order, a selfless teacher, a beautiful woman, and she’s a wonderful mother to our son. If not for her, I’d be lonely, broke, selling cars by day and drinking myself to sleep at night. I’m not sure how I got so lucky. |

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Visit Jay Baron Nicorvo… |

|||||

Stated

Stated

Reader Comments