Interview: Sy Safransky, The Sun, and the Stars Who Revolve Around It

|

|

|||||||

|

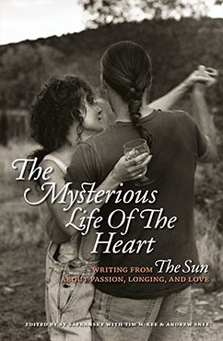

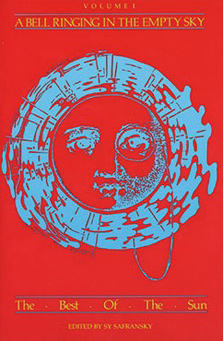

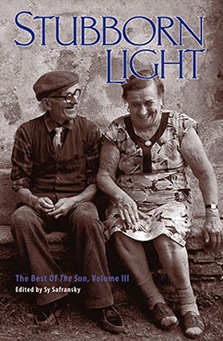

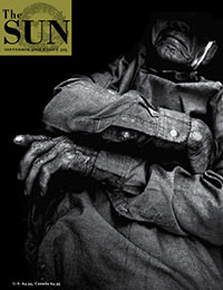

Every Word Tell: Sy Safransky, The Sun, and the Stars Who Revolve Around It Interview By Sebastian Matthews Imagine a literary magazine that brings together essays, interviews, stories, and poems, pays well for the work, invites politics and spirituality to hang out together, and publishes risky, confessional material. A journal that offers readers a forum to share their stories on themes, such as sex, death, joy, and pain (not necessarily in that order). Now give it an avid readership of more than 70,000 subscribers and, for good measure, throw in handsome design work with black-and-white photographs, full-page spreads for poetry, and an absence of distracting advertisements. Now allow its editor to write from his desk on all matters of the world and end each issue with a compendium of quotes from the great thinkers of the world. Add the fact that it publishes certain authors over and over, allowing them to grow into a long-term relationship with an avid readership, and that the journal is approaching its 35th year of existence and readily available on-line and in bookstores, grocery stores, and libraries across the country. Now imagine reading and writing groups springing up in cities and towns (and even in foreign countries) so that readers of the magazine can get together to discuss the latest issue. Writing workshops, too, where readers come together to work with the writers of the magazine. Now imagine that the magazine is called The Sun. For, indeed, it is. And its editor goes by the name Sy Safranksy. |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

“When I started The Sun,” Safransky writes, “I wanted to marry my revolutionary ardor and longing for truth with my passion for good writing. For me, putting out each issue is still a political act and an act of devotion—my spiritual path disguised as a desk job.”

There’s a popular story of how Sy peddled the first crudely produced issue (titled The Chapel Hill Sun) on the streets of Chapel Hill back in 1974. Issue number 1, titled “Energy,” carried a cover price of twenty-five cents. Safransky gave the copies away, writes L.W. Milan. “He was too embarrassed by the poor quality of the printing to ask people to pay for them. For the first couple of years The Sun barely resembled its current incarnation. To begin with, its focus was this small, funky college town populated primarily by students, professors, dropouts, and graduates. As the magazine grew, the title became simply The Sun.” “At first glance one might get the impression that The Sun is a hippy-dippy, touchy-feely, New Age publication,” notes David Budbill, a poet who has published his work in The Sun’s pages for more than 15 years. “Nothing could be further from the truth. When you look more deeply at what they publish, you see immediately their willingness to challenge all sacred assumptions, which is something you cannot say for a lot of other magazines. My secret belief is that nobody reads those ‘good, prestigious, and academic literary periodicals.’ I think they are for resume building, not for reading. Not so with The Sun. Subscribers to The Sun actually read the magazine. Imagine that!” On a shelf in Sy’s office stands a tightly packed row of magazines almost as long as the set of encyclopedias above it. Sy informs me that it is every issue of The Sun. On the far left are the earliest copies, thinner and shorter than the rest. As the years progress from left to right, the spines grow whiter, less yellowed by age. The last third is a rainbow of colors. I realize what I am looking at is more than three decades of work, the accumulated thoughts and emotions of all the writers whose words have appeared in the magazine. Sy’s lifework. We went to Chapel Hill, North Carolina to interview Sy and spoke with some of The Sun’s regular contributors over email to round out a profile of the man behind it. - Sebastian Matthews |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

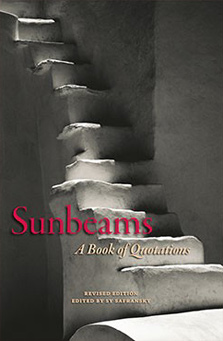

stated: Are you trying to cultivate a public relationship with your audience, or is this connection that so many readers of and writers for The Sun talk about simply a by-product of the enterprise? SAFRANSKY: We’re not selling a solution to life’s problems or presenting ourselves as any wiser than we actually are. I think of the magazine as a conversation between a writer and a reader, so I ask myself: What makes a conversation interesting? It’s when people are being genuine, when they’re more concerned with sharing difficult truths than in showing off. That’s also the approach I try to take in my ‘Notebook’ each month, because what’s the use of striking a pose? It seems to me that we’re all in the same boat—mysterious flesh-and-blood creatures, radiant and broken—and of course the boat is sinking, but there’s still time to share a story or two as the night comes on. I’m aware of the strong connection many people feel with the magazine. This is partly because of the deeply personal nature of much of what we publish—including the impassioned letters from readers and the moving and often painful confessions in ‘Readers Write.’ It’s also, I think, because we try to relate to our readers without cleverness or guile. stated: What about the bookshelf of quotations books in the corner? SAFRANSKY: [Laughs] We do have an impressive collection of anthologies on the shelves. More than most libraries, I’d guess. About three-quarters of the quotations we use in the magazine come from those books. The rest are suggested by readers, or are passages I’ve come across in my own reading. stated: Tell me about your ‘Notebook’ feature in The Sun. In our talk, you mentioned that the notebook was a way for you to keep connected to your writing—a way for you to write daily (or as near as daily as possible). Indeed, reading it I get the impression that you get up and write it in a chair each morning. How much editing do you do on these pieces? Do they come out as vignettes or do you break them into vignettes and/or whittle them down? SAFRANSKY: You’re right: I get up in the early morning darkness, pour myself a cup of black coffee, then sit down to write in my black notebook with my black pen. (If I rose at noon and used a purple pen, would my writing be less melancholic?) Some mornings, I edit as I go. Other days, I storm the hill and let the wounded fall where they may; there will be plenty of time later to dress their wounds or put them out of their misery. At the end of the month, I type up the entries that seem to have some merit. Then, trying to keep in mind the difference between being self-revealing and self-indulgent, I edit. Then I edit some more. I try to remember Strunk and White’s advice that vigorous writing be concise. “This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short,” they write, “or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.” stated: Why do you include the ‘Sunbeams’ quotes at the end of the journal? How many of these quotations come from readers? SAFRANSKY: “The word ‘Sunbeams’ might suggest mostly ‘positive’ quotations. But the quotations, while often inspiring, are hardly of the conventionally uplifting variety. Instead I look for quotations that will provoke readers to think, or to deepen their compassion, or to open a window in their mind they didn’t even know was painted shut. I used to spend hours every month (I get help with this now) sifting through hundreds of possibilities to find the right ones. Juxtaposing the quotations is like seating guests around a dinner table: Woody Allen next to Mother Teresa next to Jesse Jackson next to Anais Nin. You can’t be sure where the conversation will lead. The ‘Sunbeams’ page allows me to comment, however obliquely, on the themes running through each issue. Montaigne said he quoted others in order to better express himself. Each month, ‘Sunbeams’ lets me get in the last word. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

stated: And the ‘Readers Write’ section? SAFRANSKY: The editing of those submissions is usually more aggressive and is specifically tailored to make the entire section hold together and read well. We strive to include as many voices as we can in this chorus, and to retain every nuance of every story would take far more space than we can provide. We try to preserve the heart of each piece, although what we like best about a submission may not be the same as what the author holds dear. In the end, we need to balance the writer’s desire for expression with the need for clarity and conciseness. We give contributors the opportunity to read the edited versions, correct mistakes, and—if they can’t abide the editing—withdraw the work. We print nearly three hundred ‘Readers Write’ pieces a year; perhaps half a dozen end up being withdrawn. As a writer myself, I know how hard it is to write well; that few sentences turn out right the first time, or the second, or the third; that cranking out draft after draft is, as my friend Phil says, ‘intellectual manual labor.’ I know it can be distressing for writers, having placed a short story or an essay or a poem with us, to have their work altered. I know, too, that when a magazine tries as hard as we do to eliminate anything that might come between a writer and a reader—distracting advertising, cluttered design, not to mention the writer’s own missteps—there’s bound to be occasional overreaching. But we’re always willing to explain our reasons for changing a sentence and to be persuaded by an author’s argument to leave it the hell alone. stated: In a recent “letter to the editor,” one reader wondered what would happen to The Sun after you retired. She didn’t seem to think one entity could be separated from the other. Could you tell me a little about what you’re hoping for The Sun in the future? SAFRANSKY: I never think about retiring. The Sun is my work in the world and my work on myself; my lover; my teacher; sweat of my brow; prayer rising from my lips. It’s two cups of coffee late at night, a deadline to meet, goodnight sweetheart, see you in the morning. It’s thirty-three years of my life, seventeen hundred weeks on the job—but who’s counting? Yet I know a day will arrive when I’ll no longer climb the creaky wooden stairs to my second-floor office, and turn on my desk lamp, and get to work on the next issue. That’s because I face the same mandatory-retirement rule we all do, the one from which there’s no reprieve no matter how many hours I spend at the gym and how many vitamins I gobble. (I used to take mine in strict alphabetical order; now I throw caution to the wind and gulp a handful at a time.) For better and for worse, my temperament, intellect, and sense of moral urgency have shaped The Sun, and it’s hard for me to contemplate a future in which someone else is sitting at my desk. It’s about as appealing, I told someone recently, as imagining the kind of man my wife might marry after I’m gone. Of course, I know it won’t make a bit of difference what kind of man he is as long as he loves her, and she loves him. And I have a similar notion about my successor. You see, it’s true that I gave birth to the magazine and have nurtured it all these years. It’s equally true that the un-manifest spirit of The Sun—its energetic essence, if you will; its animating force; its primordial will-to-be—needed someone in the human realm to give birth to it, and, for whatever reason, chose me. And though I sometimes call it ‘my’ magazine, I know it’s not mine and never was mine. A Hindu saint once said that Abraham Lincoln was a great president because he knew he was only acting president. I’m no Lincoln, but at least I’ve tried to remember I’m only acting editor. If my successor remembers this, too, if my successor loves The Sun and is well loved by The Sun, what difference does it make whether he or she selects exactly the same pieces to publish that I would have selected, or insists as emphatically on serial commas, or keeps the office just as neat? So after my stubborn heart calls it a day, The Sun’s board of directors will consult with current and former staff members (and, I hope, soothsayers, magicians, and God-intoxicated poets) and select a new editor, and the radiant heart of the magazine will keep on shining. And who knows? Under a different editor’s guidance, The Sun may blaze more brightly than I can imagine. But what if it doesn’t? What if the next editor turns out to be completely wrong for the job, an arrogant fool who confuses his or her name up in lights with the light of truth, and tries to take the magazine in precisely the wrong direction? Then may all our devoted readers—those who faithfully renew their subscriptions year after year, and donate money to The Sun, and write impassioned letters about how much the magazine means to them—rise up and stone the son of a bitch. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

stated: Poe Ballantine said in an email: “Not long ago, I had an opportunity to meet staff and many readers at the 25th Sun anniversary in Chapel Hill. I thought I might not like Sy, since he is such a death-obsessed worrywart and makes fun of me for drinking boxed wine, but I was very impressed. He’s not as tall as I thought he’d be, but his eyes really twinkle and he has a fine sense of humor. I’ll add that he serves good wine from bottles.” He also added, in a more serious vein: “The Sun, of course, would not exist without Sy. You’re talking about The Doors without Morrison, Dada without Duchamp, Tibet without the Dalai Lama, or a Big Adventure without Pee Wee Herman.” Any response? SAFRANSKY: The first time I paid Poe big bucks for an essay, I got carried away and suggested he go out and buy a couple of bottles of expensive wine, for it pained me that authors of considerably less stature were uncorking vintage cabernets while he, one of the best writers in America, was drinking wine from a box. But I guess I stuck my nose where it didn’t belong. Besides, what difference will it make, when Death taps him on the shoulder, whether he’s guzzling the good stuff or not? |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

stated: I have asked a handful of other writers to tell me when they first encountered The Sun and its intrepid editor. Sparrow(poet-activist who ran for President with the slogan ‘Forgive All Debts, Free The Slaves’; created stir in 1995 when he picketed The New Yorker magazine, holding a placard reading, ‘My Poetry is as Bad as Yours’): Back in the mid-70s I worked at Mother Earth, a natural foods store in Gainesville, Florida, bagging raisins and powdered milk, ordering the bulk herbs. It was there I first saw The Sun, which I remember as being small and homemade-looking. The photographs weren’t prominent. I suppose I noted the “Us” column, where readers wrote in. The Sun did not seem so unique then. There were a number of such magazines, the most prominent being The East-West Journal, a well-written monthly published by macrobiotics. I was from the same social class as Sy, a lower-middle-class Jew from New York City, rather well educated, who dropped out of society to move to the South. The New Age then—if you can believe this—was not yet an absurd cliché, but a sub-cultural vision. A small group of ex-hippies had stumbled upon ancient wisdom that would transform the world. It sounds, I know, like the plot of a comic book. Gillian Kendall (regular contributor, editor of Something to Declare: Good Lesbian Travel Writing, now an official reader The Sun): I believe there is a recognizable Sun style. You can sort of see it in the ‘Readers Write’ section. It’s understated, although sometimes overtly emotional—that is, The Sun is not opposed to ‘telling’ about an emotion as opposed to always ‘showing.’ But I think the distinguishing mark of a Sun-edit job is in the ending. Those ‘Readers Write’ pieces seem to end somewhat abruptly (to me). I imagine that the original submission went on quite a bit longer, wrapping things up, explaining the significance a bit—but there’s nothing more shuddered at, at The Sun, than the idea of a ‘neat ending’ or, God forbid, any kind of ‘lesson’ or suggestion of meaningful conclusion. Alison Luterman(poet whose work appears regularly in The Sun): I have a sense of The Sun being read hungrily, by all kinds of people, across the U.S. and even around the world. There are places and people for whom The Sun is like a spring of clear water in a desert. It is not at all the typical lit-mag—it’s much more personal, unashamedly subjective, and a place where the political, the personal, and the spiritual are encouraged to all get in bed together. I like being published cheek-by-jowl with an interview with Thich Nhat Hanh, or an essay about hunger in America. Readers respond on a visceral, not just a literary basis, to poems and essays I have published there. Kendall: To a lot of us, Sy is something of an authority figure, a benign enlightened being. Dealing as he does in stories of the deepest, most personal nature, he seems somewhat god-like. And besides his editorial authority, Sy’s presence in person is similar to that of Ram Dass or Timothy O’Leary (when he was alive). He doesn’t talk much. He’s paying attention to the conversation, always, but I think he prefers to be a spectator rather than the center of attention. In the years of doing retreats with him, I’ve watched him and learnt to be a bit less chatty myself. I have always thought that I talked too fast, too much, and around Sy I felt like a real chatterbox, because he’s so quiet. David Budbill: The first poem I ever published in The Sun was called ‘Bugs in a Bowl.’ Not too many months after it came out, I got a photograph from a woman who lives in Marin County, California. The picture was of the quilt she had made inspired by my poem! And I got letters from readers about the poem. This has happened over and over again with me and The Sun. The subscribers to The Sun not only read the magazine, they react to and respond to what they read and often they communicate directly with the author. What could be better? About five years after I got the photograph of the ‘Bugs in a Bowl’ quilt, a box arrived here on my birthday. It was the ‘Bugs in a Bowl’ quit itself. Its maker had given it to me. We’ve been sleeping under it every summer since. And once when I was doing a reading at The Zen Center in San Francisco, the quilt maker her own self came to the reading and introduced herself; we’ve stayed in touch ever since. From a poem in The Sun came a quilt and a friendship. |

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Kendall: I don’t know of any other magazine, newspaper, or book editor who works with the author on a sentence level, even discussing nuances of punctuation. I can query any changes they have made, and ask to have my original wording reinstated, or have the change done differently. (I usually get my way, but not every time.) I feel very indulged, and very lucky, to have editors who a) care so much about every word that appears on the page and b) care what I think about their editing. Andrew has said to me more than once that it’s important to them that I am comfortable with the final piece. Sparrow: One of Sy’s brainstorms is to ‘leave ‘em laughing.’ Having ‘Sunbeams’ right at the end—which always contains some good jokes—sends the reader off with a chuckle-blessing. Kendall: At a recent Esalen workshop, Sy seemed mellower than usual. He read something he’d written—which I’ve never seen him do before. What he read had to do with allowing himself to be less disciplined that weekend, and hearing it was such a relief! I wish he’d learn to be a tiny bit slothful, letting himself sleep in on weekends, maybe blowing off the exercise/meditation routine once in a while, not being so hard on himself. But then, it’s usually what you love and admire about a person that makes you crazy, isn’t it? If Sy didn’t get up at dawn, didn’t drive himself as hard as he does, maybe there would not have been a Sun magazine, and my life would have been far less rich because of that lack.” Poe Ballantine (fiction writer, essayist): The Sun is not a unique enterprise. It is another planet. Its readers are a distinct group, like a tiny Oregon village isolated in the mountains circa 1926 with redolent marijuana bushes and lots of single vegetarian cat-owning women shouting at the drunken beasts below. Whenever I go out on tour or to read at a festival or a college, there is usually a Sun Reader or two who come out to look me up. Unwittingly, I have become part of a very rewarding community. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Visit Sy and The Sun at: |

||||||||

Sebastian Matthews

Sebastian Matthews

Reader Comments